Pregnant nude British Medical Journal 24 January 1998 |

GHISLAINE

HOWARD

a selection of critical responses

to Ghislaine Howard's work |

| Reviews

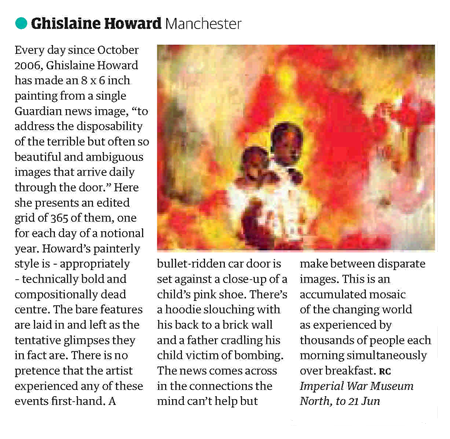

of Ghislaine Howard's exhibitions: 365 at the Imperial War Museum North, March - September 2009

|

Features

on Ghislaine Howard's working

methods:

|

| Interpretation:

Exhibiting gender - Sarah Hyde on Ghislaine Howard and Jacob Epstein - 1997 |

| Sister Wendy Becket |

| Howard's

cleavage

cuts down into a gleam of deepest

blue, the wild sea caught and held safe between the sunlit masses of

the

pure rock. It is both landscape and seascape, but it is also something

deeper. It recalls with imaginative intensity the wild spaces of the

ocean,

untamed and untameable, and the fortress of the cliffs, where the

surging

waters can gently come to rest.

In becoming aware of the beauty of the painting, we are drawn into an awareness of the beauty of repose, protection, and constant give and take of love. Howard clearly loves what she paints, and what she paints is in itself, in a strange symbolic fashion, love also. Sea and stone here unite in a dazzle of chromatic clarity. The cleft has an almost erotic splendour, but it is an eroticism of the profoundest purity. The azure of the waters reflects up onto the chalky smoothness of the cliffs, the head jutting out into the sea to enclose the wash and be purified by it. Both give; both receive; the essence of a love relationship. -

Sister Wendy Becket

(from Women Critics Select Women Artists The Bruton Street Gallery, London, 1992) |

| Richard Kendall, Galleries Ghislaine

Howard Londoners still believe themselves to be at the centre of the artistic universe, and it comes as a rude shock to discover talent existing, even flourishing, away from the capital. Ghislaine Howard has chosen to work in the north-west, within reach of two increasingly vital cultural centres, Manchester and Liverpool, but even closer to the wild and unpopulated landscapes that recur in her pictures.

In the best possible sense, these are a young person's paintings. There is energy, excess and a kind of muscularity in her canvases, untainted by cynicism and art circuit chic. Ghislaine Howard paints directly, sometimes furiously, attacking both subject and canvas with a passion for her colours and her craft. The massiveness of rocks, the swell of the sea and the tints of stormy skies are all translated into the stuff of paint, in a way that sometimes suggests late Bomberg.

-

Richard Kendall

Galleries, September 1991 |

| Jim

Aulich, City Life

Ghislaine

Howard: Recent Work Ghislaine Howard's Recent Work [shows] the dignity of the human figure and an almost French sensuality in the love and the freedom of the paint. Domestic and intimate subject-matter tells of the artist's pregnancy, and the birth and suckling of her child, while in the bath lies the image of a man in a self-conscious inversion of Bonnard's theme of the woman in the bath. Michael

in the bath 1984 Luscious and unorthodox, these pictures are strikingly original in what they depict within the context of the museum and the tradition of figure painting. -

Jim Aulich

City Life, 3 May 1985 |

Exhibiting genderAn extract from Sarah Hyde's book, Exhibiting gender, in which she compares perceptions of the portrayal of pregnancy by Ghislaine Howard and Jacob EpsteinFrom

Exhibiting gender by

Sarah Hyde, |

|

Ghislaine Howard, b 1953 Pregnant

self-portrait 1987 |

Jacob Epstein, 1880-1959 Genesis

c. 1930 |

| The

main

reason for comparing these two

works is to ask readers firstly, before looking at the answer, to

consider

whether they expect to see a difference in the way this subject is

treated

by a man and a woman, and secondly, once they know the answer, to see

if

they can detect any difference between the treatment of pregnancy by a

man, who cannot have had any personal experience of the subject, and by

a woman artist who was in fact studying her own pregnant body.

There are several important differences between these two representations. The first is that [...] one was produced over fifty years earlier than the other. Ghislaine Howard's drawing is in a style which could have been produced at almost any time this century, so that anyone who had not seen it before would probably find it very difficult to date. Nevertheless, the fact that it was produced recently is crucial to the comparison between the two works, since it is only in the last twenty years or so that significant numbers of women artists have begun to explore pregnancy, childbirth and child-rearing in their art, and such subject matter has gradually become acceptable to many art gallery visitors. Part of this development was the exhibition A Shared Experience held at Manchester City Art Gallery in 1993, which drew on work produced by Ghislaine Howard when working as an artist in residence in the maternity unit of Saint Mary's Hospital in Manchester. Howard has said that one of the greatest challenges she encountered was the fact that she felt she had no artistic tradition to draw on. She was familiar with centuries of representations of mothers and children in the 'Madonna and Child' form, and yet had never seen a Western painting of the most important subject that she was confronted with at the hospital: a woman giving birth. Further major differences between the two works can be found in their physical nature - their size and medium - and the purposes for which they were produced. Howard's drawing is under half the size of Epstein's work, and her chosen medium - charcoal - is, unless sprayed with fixative, impermanent, and has connotations of informality and privacy. The drawing, although standing as a work in its own right, was in fact part of an extensive series which led to a group of oil paintings charting the physical and psychological changes which Howard experienced during pregnancy. Epstein's work, however, was produced on a large scale in the formal and public medium of marble. These basic differences go some way towards explaining the vastly different receptions accorded to the two works when they were first produced. Howard's work caused hardly a murmur when it was purchased for the Whitworth [Art Gallery] in 1989, and likewise Epstein's work now provokes few comments from visitors to the Whitworth. When it was first displayed in 1931 at the Leicester Galleries in London, however, Genesis provoked howls of protest and abuse. The extent of the response prompted Alfred Bossom to purchase the work in order to tour it around Britain, thus raising a substantial amount of money for charity by charging a small fee to the crowds of people who flocked to see it. Subsequently the sculpture was shown alongside other works by Epstein to similarly large crowds at Louis Tussaud's Waxworks on the Golden Mile at Blackpool beach. Epstein's initial reaction, on hearing that his work was to be shown at Tussaud's, was outrage; however, he later declared himself in favour of the work being seen by as many people as possible. In making this claim, however, the artist showed himself widely out of step with much contemporary thinking about art. Reaction to an earlier work by Epstein - five figures for the British Medical Association on the Strand - had shown that most contemporary critics felt that certain types of art, and in particular nude figures, should only be seen in carefully controlled circumstances by carefully selected people. The Evening Standard declared that 'figures in an art gallery are seen, for the most part, by those who know how to appreciate the art they represent' (*Epstein 1963:23), whereas to show naked figures, as Epstein proposed, on the façade of a building in the Strand, 'To have art of the kind indicated laid bare to the gaze of all classes, young and old, in perhaps the busiest thoroughfare of the Metropolis... is another matter'. It was the duty of adult males to control and censor the kind of art to which the working classes and women were allowed access, and Epstein's nudes were 'a form of statuary which no careful father would wish his daughter, or no discriminating young man, his fiancée, to see' (Epstein 1963:23). The context in which a work of art is interpreted is, however, created not only by its physical and cultural surroundings but also by the title appended by the artist or a curator. Ghislaine Howard did not give a title to her work; the title Pregnant Self-portrait was given by a curator when it entered the Whitworth Art Gallery, and presents it as simply an artist's study of her own pregnancy. The title Genesis, however, suggests that Epstein's work is not about a particular pregnancy, or even about the subject of maternity in general, but is instead dealing with a much larger topic: the 'genesis' of the human race, a universal beginning. It was this larger aim which brought Epstein into conflict with so many people amongst Genesis' original audience. In order to express his idea of the primitive beginnings of mankind, Epstein turned for inspiration to art from Africa and the Pacific islands, of which he was a great admirer and collector. However, whereas for Epstein the work of African sculptors could suggest something fundamental, 'primitive' in the sense of marking the earliest beginnings, for contemporary reviewers the word 'primitive' meant backward, underdeveloped. This in turn constrained the way in which the expression on the face of Epstein's pregnant woman was interpreted. Whereas Epstein wanted to suggest 'calm, mindless wonder', uneducated in the sense of still being instinctual, not overlaid with the unnecessary trappings of civilisation, the racism inherent in so much of British society in the years leading up to the Second World War meant that most responses to this sculpture were conditioned by a tendency to see certain facial features - thick lips, for example - as indicative of a lack of intelligence. The Daily Express headline of 7 February 1931 ran: 'Epstein's bad joke in stone. Mongolian moron that is obscene.' (Epstein 1963:274). The choice of the word 'Mongol' here was dependent not on the actual features of Genesis herself, since Epstein based this on studies of African masks, rather than the features of the East Asian peoples of Mongolia. Instead the reference is again to the insistent link between non-Western racial types and an assumed lack of intelligence underpinning the labelling of people born with Downes Syndrome as 'Mongols' which has only recently been eradicated from common English usage. However, in the context of the subject matter of Genesis this is especially important in that non-European racial types are also presented as having not only lesser intelligence but also greater moral and sexual licence. The idea that black men are both more sexually potent and less restrained than European men can be traced back to the eighteenth century and beyond. In this context Genesis caused particular outrage in that a subject matter which Epstein's critics insisted should be treated with delicacy was mixed with associations of those qualities of 'primitive' societies which most Westerners liked to congratulate themselves on having overcome. The final insult was not only that this woman appeared to be non-European and unintelligent; she was also not beautiful, and this was if anything the most problematic issue. Epstein was violating two fundamental assumptions: that art, and women, should be beautiful. When told by a friend that most people could not understand why he had made Genesis so ugly, Epstein, with deliberately assumed incomprehension, replied that he thought she was beautiful. But in another context he made it clear that he was trying to create an image of feminity that deliberately eschewed contemporary notions of delicacy and beauty. I felt the necessity for giving expression to the profoundly elemental in motherhood, the deep down instinctive female, without the trappings and charm of what is known as feminine... How a figure like this contrasts with our coquetries and fanciful erotic nudes of modern sculpture. (Epstein 1963:139-40)Here it may be useful to draw a comparison between the response to Epstein's work and that provoked by a modern image of pregnancy. In August 1991 the front cover of Vanity Fair magazine featured a photograph by Annie Leibovitz of the naked, pregnant actress Demi Moore. It aroused a storm of protest which has been compared to that caused by the first exhibition of Genesis, but which in fact contains significant differences. Amongst the vociferous minority defending the publication of the photo were a number who thought it demonstrated that pregnant women could still be beautiful and sexy: 'what a pretty sight it is!', 'Who says women can't... retain their sexuality during pregnancy?' (Vanity Fair, October 1991:18-20). The problem here is that pregnancy entails a number of changes to a woman's body - swollen abdomen, enlarged breasts - which conflict fundamentally with the current ideal of slimness as feminine beauty, propagated by magazines such as Vanity Fair. Responses to the photo of Demi Moore demonstrated that attractiveness to men is still seen as the most important function of both art and a woman's body, in the latter case overriding any other function, such as that of producing a child. If any art form presents a pregnant woman as unattractive, for example with what the Daily Telegraph described in 1931 as Genesis' 'Face like an ape's... breasts like pumpkins... hands twice as large and gross as those of a navvy [and] hair like a ship's hawser' (Epstein 1963:276) she represents a challenge and a threat. Sarah Hyde is the Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Courtauld Gallery, University of London. * Epstein, J. , Epstein, An Autobiography(1963), ed. R. Buckle, London, Vista Books. |

Ghislaine Howard Studio Gallery

Press